My research into fast fashion, ecological design practises, principles, processes, and culture sustainability I started to think about my own cultural practices and how I would like to implement this into my own work as a future fashion designer. In this post I would like to give you an insight into the making and cultural structure around the Tongan ta’ovala. In addition to this, I will also include a review of academic texts by fashion theorist in the hope of highlighting the importance of cultural sustainability.

Jehanne Helmet-Fisk is an art historian whose research was largely based pacific island arts and crafts. Her academic journal ‘Clothes in Tradition: The ‘Ta’ovala’ and ‘Keikei’ as Social Text and Aesthetic Markers of Custom and Identity in Contemporary Tongan Society Part II’ looks into the making of ta’ovala, the different types of ta’ovala, and how ta’ovala is interpreted and used in a social context.

Ta’ovala is made out of pandanus leaves. There are different type of pandanus leaves will differ in colour – ‘paongo’ (brown), ‘tofua’ (white), ‘kie’ (white), and ‘tapahina’ (white or brown). Different types of pandanus leaves are used to make different type of ta’ovala. Please note that ta’ovala is different from ‘tapa’ or ‘ngatu’ which are commonly known type of mat that is made of tree bark – commonly referred to as bark cloth.

When preparing to make a ta’ovala, we first need to harvest the leaves from the pandanus trees and then strip them. When harvesting from the pandanus trees, it is important not to harvest from one tree/plant to not jeopardise the health of the crop. The pandanus leaves are soaked in the sea either overnight or for a couple of days to allow the leaves to bleach. Once the leaves are collected from the ocean, it is then hung out in the sun to dry. The bleached and dried leaves are rolled into bundles ready for weaving. Different type of ta’ovala will require different types of weaving techniques.

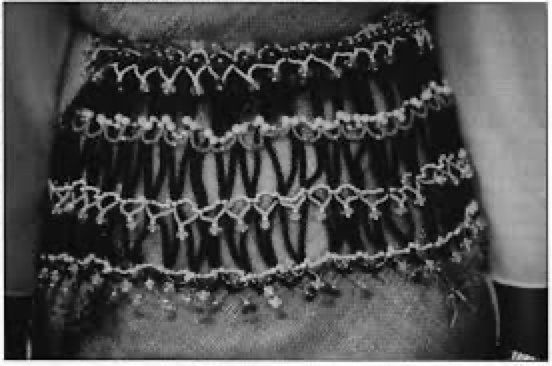

The Kie for example is one of the more intricately designed ta’ovala’s as the pandanus leaves are finer and lighter in colour. The delicate texture of the these leaves means that weavers can create different patterns as you can below. These types of ta’ovala tend to cost more due to the time and skill required. It is also a signifier of high social standing or respect when worn or being presented as a gift. Ta’ovala can be decorated with shells or feathers and following the arrival of missionaries, Tongan people used material like wool and would weave this into the ta’ovala to create patterns and add colour.

“…kie are ranked among the most highly prized. Kie is special… this preparation is ranked as being the most labour intensive and difficult and therefore exclusively used for fine mats such as the kie Tonga.”

“The wearing of a kie, particularly one that is old and finely made, always indicated the person’s standing as a member of the hierarchical ranks”

http://tonganstuff.co.nz/product/taovala-mail/

The above image is a Kie ta’ovala. You can see that the weaver has used different weaving techniques at the edge of mat for decoration.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23409091 – page 52

The above image is of a ta’ovala with a decorative Kafa. The weaving of the ta’ovala is an art form generally reserved for the women. The kafa however was historically made by the men as the plaiting technique was the same as that used in the making of ropes for boats, fishing and farming. The ta’ovala, when worn, can be layered with other ta’ovala or different types of kata for decoration.

https://678988741256098934.weebly.com/blog/category/all

The above image is an example of the layering of ta’ovala. This is wedding attire and so ta’ovala and different types of kata was ties around the waist. You can also the mat where wool is used to create pattern and to add colour and texture.

“The role of the ta’ovala, or fine mats, as indications of wealth, status, and inherited heirloom is even more evidence among the noble classes, who use it to legitimise their genealogical claims to chiefly lines and even flaunt it, at time, as a trump card in a wedding or funeral ceremony”

The above quote indicates that ta’ovala has a number of different functions. Not only is it a type of traditional clothing but it also acts a social indicator for Tongan people. These piece of clothing act as vessels to one genealogical history and when gifted from one family to another, symbolises the coming together of two families/peoples. The time and manpower that is takes to make a piece of ta’ovala means that Tongan people go to great lengths to care for each piece. When walking into a Tongan home you may find mats stores underneath mattresses as it flattens the matts and keeps it from getting damp and moulding in the moist New Zealand climate.

Susanne Kuchler and Graeme Were’s ‘Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands: The Social World of Cloth in the Pacific Islands’ explores the relationship between clothing and identity. Susanne and Graeme conclude that the history of cloth throughout the pacific has been used as a way to ‘harness and control the power contained within its textured surface’.

“Pacific societies are unique in expressing, perhaps more fervently than observed elsewhere, the centrality of cloth to identities of kinship and political authority, as cloth is harnessed and transformed into surfaces that allow for binding and dissolving of connections in the social world.”

Susanne and Graeme’s writing confirms that the cultural significance placed on cloth was reserved solely to Tonga but was prevalent throughout the Pacific. Our techniques of weaving differ from island to island however the overall ethos of respect and connection to our cultural pieces of clothing are the same. A great level of respect is paid to weavers and to the pieces that are passed down from generation to generation. I wonder whether this is a practice that can be adopted within the western context of fashion.

The theory that I have explored throughout my blog posts is the need to change our relationship with clothing. The way that we interact with clothing and the ways in which the meaning of clothing has changed over time is why and how the current systems of consumption have been able to grow into what it is today. Fashion as Communication by Malcolm Barnard is centred abound the Sender and Receiver model which explores the idea of fashion being used a way to communicate a message whether that be one of politics or personal identity.

“Given that there will be an infinite number of people, and an infinite number of groups of people, to encounter an item of fashion or clothing, there will be an infinite number of meanings constructed for an item”

I completely agree that the infinite number of people means that there will be an infinite number of interpretations towards fashion/clothing. No one person or group will have the same level of connection to a piece of clothing. This means that the cultural practices, processes and principles that have been passed down from generation to generation in the pacific may not be suitable in places like Europe etc. Although this is something to consider, it does not mean that there is nothing to gain from educating oneself on the cultural principles, practises and processes of different countries and its native peoples.

The practices in the making of cultural clothing and the cultural principles in the production process of clothing, at least in the pacific, is very much reflective of slow fashion. A piece of Ta’ovala can take from 6 to 12 months to make depending on the size and type. That fact that the craftsmanship of ta’ovala is all hand made, with the exception of wool or beading that may used as decoration, means that each pieces is unique. The production process is sustainable in that the practice of making ta’ovala requires a level of acknowledgement of the land and what you are taking from it. The materials are biodegradable and there is little to no pollution to the land. These are all things that have worked for centuries in the islands and so I believe that if we hone in on the native practices, principles and processes of each country, that we start to away from fast fashion.

In her article ‘Attentiveness, Materials, and Their Use – The stories of never washed, perfect piece and my community’, Kate critiques consumer culture and the role that it plays in the fashion industry. She proposes that although reducing the amount one consumes is a great start, that we need to address the reasons why we feel the need to consume the way do – attacking the root of the problem.

“Contemporary consumer culture, permeated with a pressure for newness and perfection, is characterised by a process of alienation from the items – the garments – we have in large numbers”…“It suggests that through fostering a deep appreciation and respect for intrinsic material qualities of things we develop an understanding of their value in ways that go beyond their usefulness to us.”

Kate accurately captures the consumer culture and the driving force behind it. Production being taken offshore, the system of ready made clothes and the pursuit for newness and perfection as resulted in an alienation/disconnect to clothes.

“Max-Neef describes this as a shift from a system where ‘life is placed at the service of artefacts (artefacts are the focus)… to [one where] artefacts [are] at the service of life.’”

The practice of thanking the land for it provides by ways of materials used in the making of clothing, the respect that paid to the environment and acknowledging that we do need to take all but only what is required, all of these are still strong in the craft of weaving. The culture principles of Tongan people, similar to that of Maori peoples (see day 4 – Treaty of Waitangi), is reflective of this idea that “life is placed at the service of artists”. I interpret this as meaning that we have an understanding that the life of land is to be protected and that we should appreciate what it gives to us and in turn should be mindful of what and how we take from life, from Mother Nature.

I would like to implement the practice of ta’ovala, the principles of weaving and would love to partake in the traditional process of making and connecting with Ta’ovala into my designs. By doing this, I believe that I will be participating the sustainability of my own culture while also partaking in environmentally sustainable methods of making and creating.

Bibliography:

Teilhet-Fisk, Jehanne. “Clothes in Tradition: The ‘Ta’ovala’ and ‘Kiekie’ as Social Text and Aesthetic Markers of Custom and Identity in Contemporary Tongan Society Part II.” Pacific Arts, no. 6 (1992): 40–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23409091.

Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation, Providing science-based solutions to protect and restore ocean health: “Ancient Art of Tonga”, 21/03/2023 – 1:46pm, https://www.livingoceansfoundation.org/ancient-art-of-tonga/

Roth, H. Ling. “4. Tonga Islanders’ Skin-Marking.”, Man 6 (1906): 6–9., 21/03/2023 – 1:58pm, https://doi.org/10.2307/2788065 , Kate “Fashion, Needs and Consumption.” In Fashion Theory, A Reader Second

Kutcher, Susanne & Were, Graeme. “The Social World of Cloth in the Pacific Island.” In Berg Encyclopedia Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands Vol 7, 380-391. Berg Publisher 2011.

Fletcher, Kate “Fashion, Needs and Consumption.” In Fashion Theory, A Reader Second Edition, 177-187. Routledge 2020.

Barnard, Malcolm “Fashion as Communication Revised.”In Fashion Theory, A Reader Second Edition, 247-258. Routledge 2020.